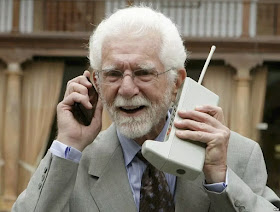

©Mark Ollig

As many of us continue working from home during the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019, commonly known as COVID-19, our need for a consistent, reliable internet connection has become essential.

While working from home, I have experienced a few internet outages, which, of course, always come at the wrong time.

The last outage happened three weeks ago.

With my internet service out, feelings of frustration came into play, which I assume some of you probably have experienced after losing your internet connection.

After waiting 10 minutes to see if the service would restore (which it didn’t), I contacted the ISP (Internet Service Provider) to calmly voice my displeasure.

Using the ISP’s Status Center app on my smartphone, I could stay up-to-date on any changes regarding the outage as new information was released.

The app recognized my exact internet location and provided a coverage map showing how widespread the outage was, and the number of subscribers affected.

The ISP also sent updated text messages to keep me apprised of the outage, its cause, and when I could expect the service to be restored.

Information provided by the app could also be forwarded to a coworker or management.

Fortunately, the internet outage did not last too long, and I was able to continue with my online workday.

Recently, our good friends at Pew Research published results of a study on Americans working from home during COVID-19.

Part of the study focused on the concerns they have about experiencing an internet or cellphone outage.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, the increased use of messaging and email has substituted for the face-to-face communications typically used at places of business outside the home.

Adults ages 18 to 49 who work from home use email and text messaging 80 percent of the time, while those aged 50 to 64 said, 71 percent. A surprise was the tech-savvy 65-and-older folks who reported in at 74 percent.

Of course, people working from home also communicate with others using video calling services, like Skype or Facetime, and online video conferencing programs, such as Zoom or WebEx.

Pew reports 32 percent of those 18 to 29 years old are communicating via video services, while 33 percent of folks age 30 to 39 are using these services. The percentage drops 11 percent for adults age 50 to 64, with 22 percent, and a reported 9 percent for adults over 65.

College graduates reported greater use of online video conferencing for work, with 46 percent saying they use it. Those with a high school education or less who use video conferencing numbered 11 percent.

The report also asked adults if they are sharing information about COVID-19 through various social media networks, such as Twitter and Facebook.

The highest percentage for sharing information belongs to adults age 18 to 29, where 44 percent responding said they do. Those 30 to 49 came in at 41 percent, while folks 50 to 64 polled at 34 percent. For adults 65 and over, 28 percent were sharing information

Our dependency on reliable internet, cellphone, and landline telecommunication services is paramount for those of us working from home.

When Pew asked how disruptive a long outage with their internet or cellphone service would be during the COVID-19 outbreak, 93 percent of adults of all ages answered by saying it would be a “very big” problem in their workday.

When broken down by ages, 53 percent of those 65 and less, see significant disruptions as a “very big problem,” as compared to 38 percent of folks 65 and older who said it would not be much of a disturbance for them.

When asked if during the COVID-19 outbreak, using online internet and phone communications would suffice for an extended period versus in-person face-to-face, 27 percent of all adults surveyed said yes.

Once they end working from home, 64 percent of all adults said phone calls, and online services would not remain their primary communication method.

Pew Research conducted its survey during the last two weeks of March. A total of 11,537 people participated.

I, personally, know of network technicians and others behind the scenes who are working hard to ensure our internet and telecommunications services remain operating at optimum efficiency, despite the dramatic increase in their use by those of us working from home.

Be safe out there.

As many of us continue working from home during the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019, commonly known as COVID-19, our need for a consistent, reliable internet connection has become essential.

While working from home, I have experienced a few internet outages, which, of course, always come at the wrong time.

The last outage happened three weeks ago.

With my internet service out, feelings of frustration came into play, which I assume some of you probably have experienced after losing your internet connection.

After waiting 10 minutes to see if the service would restore (which it didn’t), I contacted the ISP (Internet Service Provider) to calmly voice my displeasure.

Using the ISP’s Status Center app on my smartphone, I could stay up-to-date on any changes regarding the outage as new information was released.

The app recognized my exact internet location and provided a coverage map showing how widespread the outage was, and the number of subscribers affected.

The ISP also sent updated text messages to keep me apprised of the outage, its cause, and when I could expect the service to be restored.

Information provided by the app could also be forwarded to a coworker or management.

Fortunately, the internet outage did not last too long, and I was able to continue with my online workday.

Recently, our good friends at Pew Research published results of a study on Americans working from home during COVID-19.

Part of the study focused on the concerns they have about experiencing an internet or cellphone outage.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, the increased use of messaging and email has substituted for the face-to-face communications typically used at places of business outside the home.

Adults ages 18 to 49 who work from home use email and text messaging 80 percent of the time, while those aged 50 to 64 said, 71 percent. A surprise was the tech-savvy 65-and-older folks who reported in at 74 percent.

Of course, people working from home also communicate with others using video calling services, like Skype or Facetime, and online video conferencing programs, such as Zoom or WebEx.

Pew reports 32 percent of those 18 to 29 years old are communicating via video services, while 33 percent of folks age 30 to 39 are using these services. The percentage drops 11 percent for adults age 50 to 64, with 22 percent, and a reported 9 percent for adults over 65.

College graduates reported greater use of online video conferencing for work, with 46 percent saying they use it. Those with a high school education or less who use video conferencing numbered 11 percent.

The report also asked adults if they are sharing information about COVID-19 through various social media networks, such as Twitter and Facebook.

The highest percentage for sharing information belongs to adults age 18 to 29, where 44 percent responding said they do. Those 30 to 49 came in at 41 percent, while folks 50 to 64 polled at 34 percent. For adults 65 and over, 28 percent were sharing information

Our dependency on reliable internet, cellphone, and landline telecommunication services is paramount for those of us working from home.

When Pew asked how disruptive a long outage with their internet or cellphone service would be during the COVID-19 outbreak, 93 percent of adults of all ages answered by saying it would be a “very big” problem in their workday.

When broken down by ages, 53 percent of those 65 and less, see significant disruptions as a “very big problem,” as compared to 38 percent of folks 65 and older who said it would not be much of a disturbance for them.

When asked if during the COVID-19 outbreak, using online internet and phone communications would suffice for an extended period versus in-person face-to-face, 27 percent of all adults surveyed said yes.

Once they end working from home, 64 percent of all adults said phone calls, and online services would not remain their primary communication method.

Pew Research conducted its survey during the last two weeks of March. A total of 11,537 people participated.

I, personally, know of network technicians and others behind the scenes who are working hard to ensure our internet and telecommunications services remain operating at optimum efficiency, despite the dramatic increase in their use by those of us working from home.

Be safe out there.

|

| (Right to Use Clip Art image paid for) |