© Mark Ollig

A May 22, 2013, “All Things Considered,” broadcast on National Public Radio (NPR) reported a historical document; the first web page – was lost.

Tim Berners-Lee, the acknowledged inventor of The Web, created the first web page.

Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web while working at the European Organization for Nuclear Research laboratory, better known as CERN, located in Switzerland.

Paul Jones, a clinical professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), intently listened to the 2013 NPR radio broadcast and became surprised upon hearing its report.

In his March 1989 proposal submitted to CERN, Berners-Lee described writing a 1980 computer program for keeping track of software in a data server system called Enquire.

The computer program “... allowed one to store snippets of information, and to link related pieces together in any way. To find information, one progressed via the links from one sheet to another,” Berners-Lee described.

Berners-Lee diagramed a flowchart showing how users of the CERN network could distribute, access, and collaborate on documents within electronic files located on various data servers.

Electronic documents could be viewed and modified by a user, no matter which type of computer or operating system they used.

Berners-Lee wrote about a generic client browser software program that allows a CERN networked computer station user to access, change, and save hypertext data stored on other networked computers.

Ted Nelson coined the word, hypertext, in the early 1960s, describing his Project Xanadu, which never became a working reality for him until 2014.

“Most systems available today use a single database. This is accessed by many users by using a distributed file system,” Berners-Lee wrote in 1989.

A single database could store a lot of information; however, he stated it was all in one place.

Berners-Lee would create protocols for a computer to link to and connect with different computer databases storing electronic documents on a shared network, no matter where they resided.

Berners-Lee’s proposal to his colleagues more than 30 years ago was the foundation for today’s World Wide Web, aka The Web.

Berners-Lee and his colleague, Robert Cailiau, began work Nov. 12, 1990, on a proposal for making hypertext accessible via a gateway over the internet.

“WorldWideWeb: Proposal for a HyperText Project,” is the name of their written proposal presented to CERN.

Dec. 25, 1990, Berners-Lee finished the software program he called WorldWideWeb (spelled with no spaces) and had it up-and-running on his NeXTcube computer server.

According to NPR, in 2013, the first web page was lost, but someone did have a copy of Berners-Lee’s original.

Yes, it was Paul Jones, who, in 1991, stored a copy of the famous original web page on his NeXTcube computer at UNC.

How did Jones obtain Berners-Lee’s first web page?

The backstory to Jones having a copy of the first web page is when Berners-Lee visited Jones at UNC at Chapel Hill while en route to a 1991 “Hypertext ‘91” conference in San Antonio, TX to demonstrate his new World Wide Web project.

Jones was interested in a database search software called Wide Area Information Servers (WAIS), developed by Thinking Machines, Inc. out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Berners-Lee was also interested in WAIS technology and became acquainted with Jones through a mutual colleague.

“When Tim [Berners-Lee] did come to visit, he already knew that I, too, had a NeXTcube workstation computer just like his,” said Jones.

Berners-Lee used the NeXTcube computer to create the first web page at CERN.

“We talked about WAIS and WorldWideWeb software. He [Tim Berners-Lee] pulled out a floptical drive [read-write optical disk]. I installed Tim’s graphical browser [from the disk] on my NeXTcube computer. He talked me through using the WorldWideWeb software with a copy of his Hypertext ‘91 demonstration web page,” Jones said.

Berners-Lee’s Hypertext ‘91 demonstration webpage is the first web page.

After the 2013 broadcast, Jones told NPR and CERN that he knew the location of the 1991 original copy of Berners-Lee’s first web page.

Years before 2013, Jones archived data files from his NeXTcube computer onto the digital library and archive computer server, originally known as SunSITE, on the publicly accessible UNC computer server.

You may have correctly guessed the archived data included the first web page files from Berners-Lee’s optical disk still copied onto the hard drive in Jones’ NeXTcube computer.

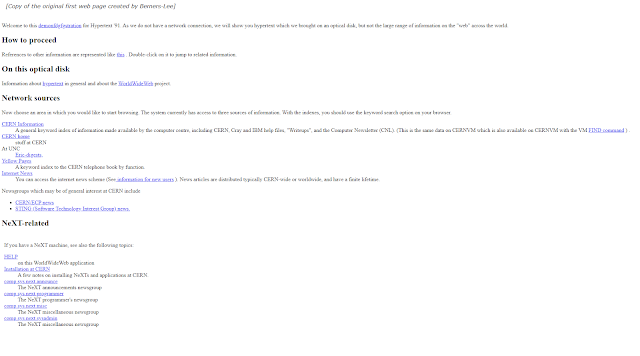

The historical copy of the original first web page (with hypertext) created by Berners-Lee is viewable at https://bit.ly/3iVAPPm.

Tim Berners-Lee’s 1989 proposal is on the World Wide Web Consortium’s website, https://bit.ly/2eOwOYN.

SunSITE became Ibiblio. The website is http://www.ibiblio.org.

Today, Jones is the director of ibiblio.org, a contributor-run, online digital library of public domain and creative commons media. He is also a clinical professor in the School of Information and Library Science and at UNC School of Media and Journalism.

Jones was the co-chair of the 2010 International World Wide Web Conference.

Thanks, Paul, for saving this historical web page document for future generations to look back on.