© Mark Ollig

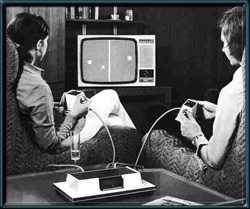

Do you remember playing Pong on a television set during the mid-1970s?

For my younger readers, Pong is a table tennis video game designed in 1972, by Allan Alcorn, an engineer who worked for Atari Inc.

The first commercial cabinet version of Alcorn’s arcade video game was installed in September 1972 at Andy Capp’s Tavern in Sunnyvale, CA.

This installation was a test to see how the public would respond to playing the game.

“Deposit quarter. [tennis] Ball will serve automatically. Avoid missing ball for high score,” read the printed instructions.

Pong became extremely popular among the local patrons at Andy Capp’s Tavern.

However, two weeks after its installation, the video arcade machine began having problems.

A phone call from the tavern manager was made to Atari, saying the Pong game stopped operating.

Allen Alcorn came out to investigate.

When he opened the arcade cabinet, he discovered Pong was not working because quarters were backed up and jammed into the machine’s mechanical mechanism.

The metal coin box overflowed due to a large number of quarters filling it up faster than it could be emptied.

This story took me back to the days when part of my job was repairing public payphones.

Sometimes, a payphone would become “out of order” due to quarters, dimes, or nickels becoming lodged inside the coin chute assembly.

Other times, the payphone was not working due to someone becoming frustrated during a conversation and pulling the handset cord from the payphone’s cabinet housing – but that is a topic for a future column.

However, I digress.

The Christmas season of 1975, Sears sold Home Pong (using a game console) for $98.95.

Pong’s game console connected to any TV, though the game looked better when played on a color set.

In 1966, Ralph H. Baer wrote a four-page outline for a game control box that could connect to any standard TV. Two people could use individual controllers to play a variety of electronic games, including ping-pong, tennis, handball, volleyball, and others.

Electronics- and TV-maker, Magnavox bought Baer’s technical design and the two-player controllers and box. They named it the Magnavox Odyssey video game console.

In November 1972, Magnavox began home distribution of the Magnavox Odyssey game console. More than 130,000 game consoles sold the first year.

However, there was an identification problem with the Magnavox video game console.

A growing number of people believed the Magnavox Odyssey console would only work on a Magnavox television set.

Atari picked up on this and attempted to use it to their advantage.

They began printing the following on all their Home Pong advertising, packaging, and game boxes: “Works on any television set, black-and-white, or color.”

Magnavox quickly adjusted their advertising, informing the video-game-buying consumer that their game console worked on any manufacturer’s television set.

In 1961, a video game called Spacewar! was created by four Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) students.

The video game operated over MIT’s DEC PDP-1 (Digital Equipment Company Programmed Data Processor) computer.

Steve Russell completed the final software code programming for Spacewar!, while Dan Edwards, Peter Samson, and Martin Graetz are credited with adding additional features.

The PDP-1 emulator for playing the video game is at http://spacewar.oversigma.com.

In 1958, William Higinbotham worked as the instrumentation division head at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, NY.

To entertain visitors to the laboratory, he created a video game, called Tennis for Two, using an electronic oscilloscope connected to an analog computer.

In 1952, the first digital graphical tic-tac-toe game was called OXO. A person played against a computer in a tic-tac-toe game on a British-made Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) computer, initially constructed in 1948.

The human player uses a rotary phone dial as the OXO game controller.

I can hear it now: “What’s a rotary phone dial, grandpa?”

A player dials a digit from 1 to 9 to represent the location of where to place an X or O on the tic-tac-toe board displayed on the computer’s cathode ray tube (CRT) screen.

Alexander S. Douglas wrote the programming code for OXO at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

To view a screenshot of an EDSAC simulator running the OXO game, go to https://bit.ly/2QLbrh8.

The inspiration for screen-based video games may have originated during World War II, with electronic radar display images.

US Patent 2,455,992 “Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device” was filed Jan. 25, 1947, by Thomas T. Goldsmith Jr. and Estle Ray Mann.

“One or more targets, such as pictures of airplanes, are placed upon the face of the [CRT] tube. Controls are available to the player so [they] can manipulate the trace or position of the beam, which is automatically caused to move across the face of the tube,” read text from the patent.

The tracing of the electron light beam on the display screen has been compared to how the Etch A Sketch drawing toy (released in 1960) operates.

US Patent 2,455,992 can be seen at https://bit.ly/2XPiiaW.

Anybody have a quarter I can borrow to play an arcade video game? Oh, wait. I have an app for Pong on my smartphone.

Do you remember playing Pong on a television set during the mid-1970s?

For my younger readers, Pong is a table tennis video game designed in 1972, by Allan Alcorn, an engineer who worked for Atari Inc.

The first commercial cabinet version of Alcorn’s arcade video game was installed in September 1972 at Andy Capp’s Tavern in Sunnyvale, CA.

This installation was a test to see how the public would respond to playing the game.

“Deposit quarter. [tennis] Ball will serve automatically. Avoid missing ball for high score,” read the printed instructions.

Pong became extremely popular among the local patrons at Andy Capp’s Tavern.

However, two weeks after its installation, the video arcade machine began having problems.

A phone call from the tavern manager was made to Atari, saying the Pong game stopped operating.

Allen Alcorn came out to investigate.

When he opened the arcade cabinet, he discovered Pong was not working because quarters were backed up and jammed into the machine’s mechanical mechanism.

The metal coin box overflowed due to a large number of quarters filling it up faster than it could be emptied.

This story took me back to the days when part of my job was repairing public payphones.

Sometimes, a payphone would become “out of order” due to quarters, dimes, or nickels becoming lodged inside the coin chute assembly.

Other times, the payphone was not working due to someone becoming frustrated during a conversation and pulling the handset cord from the payphone’s cabinet housing – but that is a topic for a future column.

However, I digress.

The Christmas season of 1975, Sears sold Home Pong (using a game console) for $98.95.

Pong’s game console connected to any TV, though the game looked better when played on a color set.

In 1966, Ralph H. Baer wrote a four-page outline for a game control box that could connect to any standard TV. Two people could use individual controllers to play a variety of electronic games, including ping-pong, tennis, handball, volleyball, and others.

Electronics- and TV-maker, Magnavox bought Baer’s technical design and the two-player controllers and box. They named it the Magnavox Odyssey video game console.

In November 1972, Magnavox began home distribution of the Magnavox Odyssey game console. More than 130,000 game consoles sold the first year.

However, there was an identification problem with the Magnavox video game console.

A growing number of people believed the Magnavox Odyssey console would only work on a Magnavox television set.

Atari picked up on this and attempted to use it to their advantage.

They began printing the following on all their Home Pong advertising, packaging, and game boxes: “Works on any television set, black-and-white, or color.”

Magnavox quickly adjusted their advertising, informing the video-game-buying consumer that their game console worked on any manufacturer’s television set.

In 1961, a video game called Spacewar! was created by four Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) students.

The video game operated over MIT’s DEC PDP-1 (Digital Equipment Company Programmed Data Processor) computer.

Steve Russell completed the final software code programming for Spacewar!, while Dan Edwards, Peter Samson, and Martin Graetz are credited with adding additional features.

The PDP-1 emulator for playing the video game is at http://spacewar.oversigma.com.

In 1958, William Higinbotham worked as the instrumentation division head at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, NY.

To entertain visitors to the laboratory, he created a video game, called Tennis for Two, using an electronic oscilloscope connected to an analog computer.

In 1952, the first digital graphical tic-tac-toe game was called OXO. A person played against a computer in a tic-tac-toe game on a British-made Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) computer, initially constructed in 1948.

The human player uses a rotary phone dial as the OXO game controller.

I can hear it now: “What’s a rotary phone dial, grandpa?”

A player dials a digit from 1 to 9 to represent the location of where to place an X or O on the tic-tac-toe board displayed on the computer’s cathode ray tube (CRT) screen.

Alexander S. Douglas wrote the programming code for OXO at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

To view a screenshot of an EDSAC simulator running the OXO game, go to https://bit.ly/2QLbrh8.

The inspiration for screen-based video games may have originated during World War II, with electronic radar display images.

US Patent 2,455,992 “Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device” was filed Jan. 25, 1947, by Thomas T. Goldsmith Jr. and Estle Ray Mann.

“One or more targets, such as pictures of airplanes, are placed upon the face of the [CRT] tube. Controls are available to the player so [they] can manipulate the trace or position of the beam, which is automatically caused to move across the face of the tube,” read text from the patent.

The tracing of the electron light beam on the display screen has been compared to how the Etch A Sketch drawing toy (released in 1960) operates.

US Patent 2,455,992 can be seen at https://bit.ly/2XPiiaW.

Anybody have a quarter I can borrow to play an arcade video game? Oh, wait. I have an app for Pong on my smartphone.

|

| Magnavox Odyssey with game controllers and console |

|

| Magnavox Odyssey |

|

| Spacewar! |

|

| OXO was first digital graphical tic-tac-toe game (EDSAC simulator running the OXO game) |

|

| “Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device” |