© by Mark Ollig

On June 1, 1971, Judge Earl R. Larson oversaw the start of the Honeywell vs. Sperry Rand patent infringement case in Minneapolis.

The case focused on Honeywell’s legal challenge against Sperry Rand regarding its US Patent No. 3,120,606 for the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer), which was then considered the first electronic digital computer.

In 1943, John William Mauchly and John Presper Eckert began building the ENIAC digital computer.

They completed the computer in 1947 and were subsequently granted US Patent No. 3,120,606.

In 1950, Sperry Rand acquired the Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation from John Mauchly and John Presper Eckert, along with their patent.

The following year, Sperry Rand changed the name of an updated ENIAC to UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer).

However, we need to go back to 1937 when John Atanasoff and Clifford Berry began working on their electronic digital computer in the physics building at Iowa State College.

By 1939, a fully-functional electronic digital computer prototype solving linear equations and mathematical problems using binary calculations was completed.

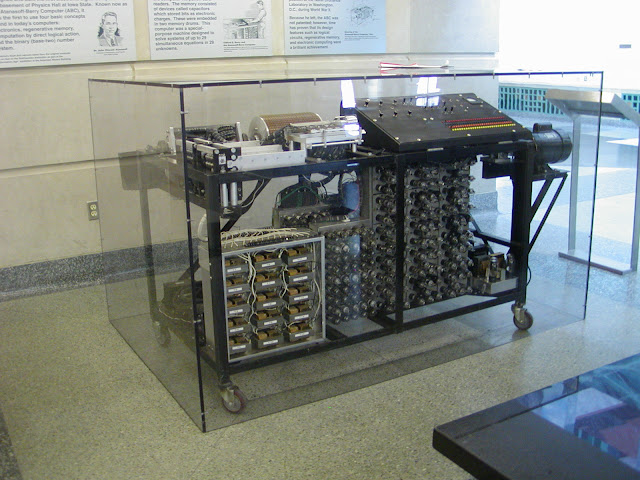

Atanasoff and Berry named their computing system the Atanasoff-Berry Computer (ABC).

The ABC became fully operational in 1942, one year before Mauchly and Eckert began work on the ENIAC.

During the 1971 patent infringement court case, testimony from John Atanasoff was presented by Honeywell, Inc.

Sperry Rand was demanding royalty payments from computer makers, arguing they alone owned the patent of the first electronic digital computer.

John Atanasoff provided evidence and testimony (Clifford Berry passed away eight years earlier at age 45) to prove Sperry Rand’s patent was not for the first electronic digital computer.

During the court case, it was revealed John Mauchly obtained engineering designs and other information about the Atanasoff-Berry Computer when he visited Iowa State College in June 1941 and met with John Atanasoff and Clifford Berry.

Mauchly acknowledged being in Ames, IA, from June 13 to 18, 1941, at the home of John Atanasoff. He discussed computer theory and design with Atanasoff and Berry during this time.

John Mauchly verified that he studied the Atanasoff-Berry Computer in Iowa State College’s physics building.

On Oct. 19, 1973, the Minneapolis Court concluded in a 248-page decision that John William Mauchly and John Presper Eckert Jr. incorporated designs from the Atanasoff-Berry Computer in developing the ENIAC.

The US Minneapolis federal court judge had ruled in favor of Honeywell.

Judge Earl R. Larson concluded, “Eckert and Mauchly did not themselves first invent the automatic electronic digital computer, but instead derived that subject matter from one Dr. John Vincent Atanasoff.”

Larson concluded that Atanasoff and Berry had initially designed a functional prototype of an electronic digital computer using basic principles.

And so, John Vincent Atanasoff and Clifford Edward Berry are recognized as the original inventors of the first electronic digital computer, thus ushering in the modern computer industry.

So, who legally holds the computer patent?

According to the court ruling, nobody had the patent rights to the computer, resulting in Sperry Rand’s ENIAC/UNIVAC computer patent being invalidated and their legal right to charge royalties being terminated.

Anyone can build a computer without paying royalties.

It’s worth noting that computer software patents can be obtained. In 2022, the top 15 software companies were awarded 50,981 US patents.

John William Mauchly died Jan. 8, 1980, at age 72.

On June 3, 1995, John Presper Eckert, Jr., passed away at 76.

John Vincent Atanasoff died at age 91 June 15, 1995.

A year before John Atanasoff passed away, a group from Iowa State University and Ames Laboratory began rebuilding a replica of the Atanasoff-Berry Computer.

Original parts from the computer, such as a memory drum and vacuum tubes, were found in storage at Iowa State University.

The group also referred to John Atanasoff's engineering design notes.

On Oct. 8, 1997, a working replica of the Atanasoff-Berry Computer was successfully demonstrated, serving as both a tribute and validation of the pioneering work of John Vincent Atanasoff and Clifford Edward Berry, who built the first-ever electronic digital computer.

In a 1984 interview, Atanasoff said, “He [John Mauchly] told me he had invented a new method of computing that was different from mine and much better. I believed him. All I want is for the world to know the truth about what I did.”