© Mark Ollig

Dec. 9 marks the 51st anniversary of a computing demonstration that was truly ahead of its time.

Douglas Engelbart dreamed of a computerized, interactive workstation while serving in the US Navy as a radar operator, shortly after World War II had ended.

In the Navy, he worked with radar images on a CRT (cathode ray tube) display screen.

Engelbart envisioned having computer data processing power accessibility available at an individual’s work station, and viewable using a CRT monitor.

The large vacuum-tube that operated computers during the 1940s had names such as Colossus, ENIAC, and Z4.

Engelbart believed individual computing work stations could be networked, thus allowing information to be quickly shared and collaborated on with others.

In 1957, Engelbart was employed at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) as a researcher.

From 1959 to 1960, with financial assistance from the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research, he worked on his project for an individual computing workstation.

“The objective of this project is to provide organization and stimulation in the search for new and better ways to obtain digital manipulation of information,” Engelbart wrote Oct. 30, 1959.

By 1962, Engelbart completed work on a computer system called the NLS (oN-Line System) using funds provided by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Dec. 9, 1968, the results of his work were publically presented during The Fall Joint Computer Conference at Brooks Hall in San Francisco, CA.

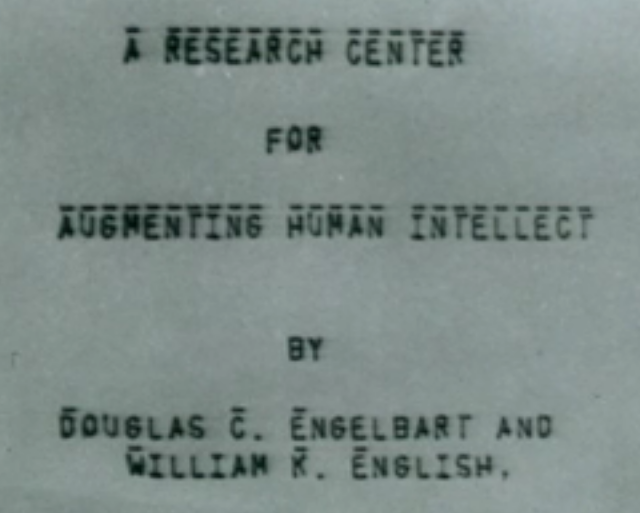

Using an NLS with a connected interactive multi-console display system (computing workstation), Engelbart gave a demonstration he called, “A Research Center for Augmenting Human Intellect.”

Engelbart presented a fascinating working demonstration into the future of human-computer interaction and networking before an audience of engineers, computer scientists, and others.

Engelbart was seated on stage in front of a terminal console screen and keyboard attached to a 22-foot video projector.

The terminal console was remotely linked via dedicated telephone lines to a mainframe computer performing the actual program processing. This computer was located 30 miles away, inside the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, CA.

Approximately 1,000 people in attendance watched the large screen above the stage – seeing what was being displayed on the terminal console monitor screen as Engelbart typed on the keyboard.

Many in the audience became curious about the “pointing device” Engelbart used to move the cursor (moveable indicator) dot on the monitor screen to highlight data being displayed.

Engelbart called the device a “mouse.”

Yes, he invented the point-and-click device we use today, and still call a mouse.

Engelbart worked on the first mouse prototype five years before the 1968 demo.

Why call it a “mouse?” It was said, someone suggested this name in 1963, because the cord connected to it looked like a tail, and the wooden, hand-held device was small, so they affectionately called it a mouse.

Unfortunately for Engelbart, the patent for his mouse creation was owned by the company where he developed it: Stanford Research Institute.

He never received any monetary royalties for this invention, but the computing world acknowledges him with inventing it.

Engelbart received many prestigious awards over his lifetime for his work in computer technology, and of course, for inventing the computing mouse.

In one interview, Engelbart thought they would have come up with a more official-sounding description for the mouse; but acknowledged the device would always be known as a “mouse.”

While watching a video of the 1968, 90-minute Engelbart demonstration, one of the things which impressed me – besides the technology – was the professionalism Engelbart exuded throughout the entire presentation.

Fascination showed on the faces of those in attendance, while Engelbart explained and demonstrated the way hypertext links between files worked, and how to use statement coding to manage and organize file folder directories, and sub-files.

During the presentation, Engelbart quickly typed statement code software programs on-the-fly, using the built-in keyboard inside the computer console.

He demonstrated how one could manipulate and organize the information contained inside text files.

Using “computer screen windowing,” Engelbart showed how one could simultaneously view separate information categories by displaying them inside overlaid “windows” using a single display monitor.

User-to-user video conferencing over the computing console’s monitor screen was demonstrated by Engelbart.

The real-time video conference was established by Engelbart with his coworkers located in Menlo Park. It was eerily similar to today’s video conferencing programs, such as Facetime or Skype.

Remember, folks – this technology was being demonstrated before a live audience in 1968.

People watched his presentation with amazement and gave Engelbart resounding applause at its conclusion.

Many of the researchers who worked with Engelbart from SRI went on to work at the Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center).

In 1973, they built the Xerox Alto computer, which I wrote about in my April 13 column of last year.

The Alto used a user-friendly GUI (graphical user interface), which took advantage of Engelbart’s mouse device for navigating through software programs.

Engelbart believed the use of computers would make the world a better place – and he was right.

Unfortunately, operating his 1968 NLS workstation computer system was never fully understood by the general public.

It was said, the statement coding used for creating and managing the computer program’s workstation files was too complicated for the average person to grasp.

In his later years, Engelbart spoke before students at universities, gave keynote speeches, and was interviewed countless times.

Douglas C. Engelbart passed away July 2, 2013, at the age of 88.

The Dec. 9, 1968 video presentation of The Mother of All Demos is stored within the Internet Archive and can be seen at http://tinyurl.com/1968demo.

Dec. 9 marks the 51st anniversary of a computing demonstration that was truly ahead of its time.

Douglas Engelbart dreamed of a computerized, interactive workstation while serving in the US Navy as a radar operator, shortly after World War II had ended.

In the Navy, he worked with radar images on a CRT (cathode ray tube) display screen.

Engelbart envisioned having computer data processing power accessibility available at an individual’s work station, and viewable using a CRT monitor.

The large vacuum-tube that operated computers during the 1940s had names such as Colossus, ENIAC, and Z4.

Engelbart believed individual computing work stations could be networked, thus allowing information to be quickly shared and collaborated on with others.

In 1957, Engelbart was employed at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) as a researcher.

From 1959 to 1960, with financial assistance from the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research, he worked on his project for an individual computing workstation.

“The objective of this project is to provide organization and stimulation in the search for new and better ways to obtain digital manipulation of information,” Engelbart wrote Oct. 30, 1959.

By 1962, Engelbart completed work on a computer system called the NLS (oN-Line System) using funds provided by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Dec. 9, 1968, the results of his work were publically presented during The Fall Joint Computer Conference at Brooks Hall in San Francisco, CA.

Using an NLS with a connected interactive multi-console display system (computing workstation), Engelbart gave a demonstration he called, “A Research Center for Augmenting Human Intellect.”

Engelbart presented a fascinating working demonstration into the future of human-computer interaction and networking before an audience of engineers, computer scientists, and others.

Engelbart was seated on stage in front of a terminal console screen and keyboard attached to a 22-foot video projector.

The terminal console was remotely linked via dedicated telephone lines to a mainframe computer performing the actual program processing. This computer was located 30 miles away, inside the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, CA.

Approximately 1,000 people in attendance watched the large screen above the stage – seeing what was being displayed on the terminal console monitor screen as Engelbart typed on the keyboard.

Many in the audience became curious about the “pointing device” Engelbart used to move the cursor (moveable indicator) dot on the monitor screen to highlight data being displayed.

Engelbart called the device a “mouse.”

Yes, he invented the point-and-click device we use today, and still call a mouse.

Engelbart worked on the first mouse prototype five years before the 1968 demo.

Why call it a “mouse?” It was said, someone suggested this name in 1963, because the cord connected to it looked like a tail, and the wooden, hand-held device was small, so they affectionately called it a mouse.

Unfortunately for Engelbart, the patent for his mouse creation was owned by the company where he developed it: Stanford Research Institute.

He never received any monetary royalties for this invention, but the computing world acknowledges him with inventing it.

Engelbart received many prestigious awards over his lifetime for his work in computer technology, and of course, for inventing the computing mouse.

In one interview, Engelbart thought they would have come up with a more official-sounding description for the mouse; but acknowledged the device would always be known as a “mouse.”

While watching a video of the 1968, 90-minute Engelbart demonstration, one of the things which impressed me – besides the technology – was the professionalism Engelbart exuded throughout the entire presentation.

Fascination showed on the faces of those in attendance, while Engelbart explained and demonstrated the way hypertext links between files worked, and how to use statement coding to manage and organize file folder directories, and sub-files.

During the presentation, Engelbart quickly typed statement code software programs on-the-fly, using the built-in keyboard inside the computer console.

He demonstrated how one could manipulate and organize the information contained inside text files.

Using “computer screen windowing,” Engelbart showed how one could simultaneously view separate information categories by displaying them inside overlaid “windows” using a single display monitor.

User-to-user video conferencing over the computing console’s monitor screen was demonstrated by Engelbart.

The real-time video conference was established by Engelbart with his coworkers located in Menlo Park. It was eerily similar to today’s video conferencing programs, such as Facetime or Skype.

Remember, folks – this technology was being demonstrated before a live audience in 1968.

People watched his presentation with amazement and gave Engelbart resounding applause at its conclusion.

Many of the researchers who worked with Engelbart from SRI went on to work at the Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center).

In 1973, they built the Xerox Alto computer, which I wrote about in my April 13 column of last year.

The Alto used a user-friendly GUI (graphical user interface), which took advantage of Engelbart’s mouse device for navigating through software programs.

Engelbart believed the use of computers would make the world a better place – and he was right.

Unfortunately, operating his 1968 NLS workstation computer system was never fully understood by the general public.

It was said, the statement coding used for creating and managing the computer program’s workstation files was too complicated for the average person to grasp.

In his later years, Engelbart spoke before students at universities, gave keynote speeches, and was interviewed countless times.

Douglas C. Engelbart passed away July 2, 2013, at the age of 88.

The Dec. 9, 1968 video presentation of The Mother of All Demos is stored within the Internet Archive and can be seen at http://tinyurl.com/1968demo.

|

| The terminal console Douglas Engelbart used for the 1968 public demonstration. The text is shown as it appeared on the large screen above the stage. |

|

| The terminal console Douglas Engelbart used for the 1968 public demonstration. |