© Mark Ollig

Sony announced its first PlayStation game console May 11, 1995, at the Electronic Entertainment Expo in Los Angeles, CA.

By August of that year, I was in an electronics showroom looking for the latest state-of-the-art notebook computer.

People were checking out Sony’s Watchman FD-210, Sega Saturn, Discman, and the Panasonic Shockwave Portable CD Player.

Many shelves were also lined with computers.

In 1995, I made it a weekly ritual to watch “Computer Chronicles,” a television program hosted by Stewart Cheifet since 1983.

This program served as a gateway to the constantly advancing world of personal computing technology by highlighting the latest innovations.

The show aired during the peak of the personal computing revolution, which many of us were a part of.

Cheifet’s presentations inspired me to learn more about the latest computing technology.

I remember checking out the notebooks on display in the computer showroom, such as the IBM Toshiba Satellite, Apple PowerBook, and Hewlett-Packard OmniBook.

While I was browsing, a salesman approached and asked, “Can I assist you in finding anything?”

“I’m looking to buy a portable notebook computer,” I replied.

The salesman smiled and asked for more details; I could tell he anticipated a big sale.

“I’ll need the Windows 95 operating system, Microsoft Office 95, communication software, a web browser, and a few games,” I told him.

The Microsoft Office 95 bundle was a must-have, as it included Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and Outlook email.

After the salesman showed me some of the notebook computers, I decided on the Hewlett-Packard (HP) OmniBook 4000CT, which measured 11.6 by 8.9 by 1.93 inches and weighed 6.7 pounds.

It included the Intel 100 MHz 486DX4 processor, a full keyboard, a 3.5-inch floppy drive, 16 MB of RAM, and a 520 MB hard drive.

There was a 32 MB RAM and an 810 MB hard drive option, but I thought, “Who needs that much?”

At the time, 520MB was substantial, offering more than enough space to store my operating system, office, and utility software, Netscape Navigator web browser, ProComm communications program, documents, photos, and audio files.

I can imagine young people reading this column on their smartphones, smiling at my being impressed with 520 MB of disk storage while sipping their espressos.

The OmniBook had a 10.4-inch diagonal Thin-Film Transistor (TFT) active-matrix display with a vibrant 640 by 480 resolution that was quite impressive when compared to the older laptop screens I had seen. The colors popped; the text was razor-sharp.

It also contained a rechargeable nickel-metal hydride battery that could keep it powered for up to three hours.

The cost of my new notebook computer and software was slightly more than $3,000 (equivalent to $6,100 this year).

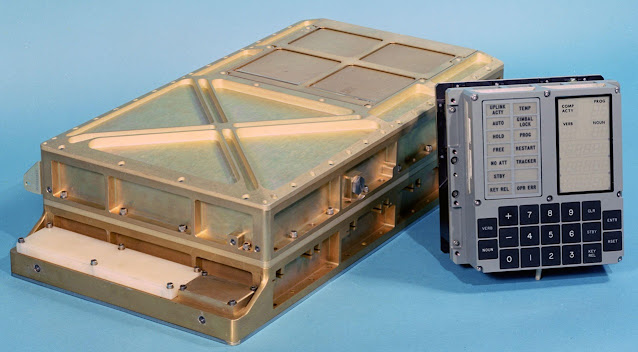

Since I am retired with more time on my hands, I decided to test NASA’s 15-pound., 8-by-8-by-7-inch Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) specifically developed for the Apollo missions to the moon, against my OmniBook.

I ran the technical specs of both the OmniBook 4000CT and the AGC through an AI program.

The specialized design of AGC was well-suited for real-time data processing, enabling split-second calculations and adjustments for navigation and control.

Its core rope memory, a form of non-volatile storage, made it remarkably reliable.

The AGC had built-in redundancy, fault-tolerant code, and error detection features, along with software programs intermixed with the Apollo spacecraft guidance systems.

The AGC “Colossus” fixed memory software system processed substantial amounts of mission data and calculated space flight and orbital trajectory information for the Apollo astronauts.

The “Luminary 1-D” also a fixed memory AGC software, calculated the maneuvers, managed navigation and control, and provided crucial information to guide the Apollo lunar module during its descent and landing on the moon.

Despite the resources of my OmniBook 4000CT computer, it could not outperform the overall abilities of NASA’s AGC.

Even with its 1960s components – a 2.048 MHz clock, 2048 words of magnetic-core RAM, magnetic-core rope ROM, integrated circuits, and specialized software – the AI program concluded that the AGC would outpace my OmniBook in calculating trajectories for a moon trip.

The Apollo Guidance Computer’s primary input and output interface used a display and keyboard unit known as a DSKY (pronounced diskey).

The DSKY screen included a 21-digit display and a 19-button keyboard.

It used a special command language which included two-digit numbers for programs, verb and noun codes, and five-digit numbers represented specific data like location or speed.

Each Apollo Command Module had one AGC and two DSKYs, which, during the early 1960s, resourceful MIT engineers designed, and the Raytheon Company built.

The Apollo Guidance Computer played a vital role in the moon missions, but its success was supported by powerful IBM System/360 mainframe computers.

Located in the Real-Time Computer Complex (RTCC) at the mission control center in Houston, TX, these computers handled complicated calculations and “mission-critical” data.

Sipping my coffee and reminiscing about my old OmniBook made me realize that much of the journey has been more than just comparing megabytes and processors.

|

| The Apollo Guidance Computer and the DSKY |

|

| My Apollo display and keyboard unit aka DSKY |